Since the launch of Chrome extensions, the platform has allowed developers to expose extension functionality directly in the top level Chrome UI using actions. An action is an icon button that can open a popup or trigger some functionality in the extension. Historically, Chrome supported two types of actions, browser actions and page actions; Manifest V3 changed this by consolidating their functionality in a new chrome.action API.

A short history of extension actions

While chrome.action itself is new in Manifest V3, the basic functionality it provides dates back

to when extensions first landed in stable in January, 2010. The first stable

release of Chrome's extensions platform supported two different kinds of actions: browser

actions and page actions.

Browser actions allowed extension developers to display an icon "in the main Google Chrome toolbar, to the right of the address bar" (source) and provided users an easy way to trigger extension functionality on any page. Page actions, on the other hand, were intended to "represent actions that can be taken on the current page, but that aren't applicable to all pages" (source).

In other words, browser actions gave extension developers a persistent UI surface in the browser while page actions appeared only when the extension could do something useful on the current page.

Both types of actions were optional, so an extension developer could opt to provide either no actions, a page action, or a browser action (specifying multiple actions isn't allowed).

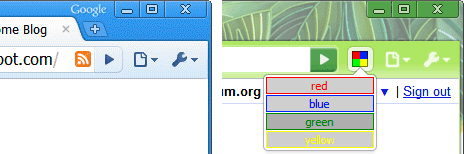

Roughly six years later, Chrome 49 introduced a new UI paradigm for extensions. In order to help users understand what extensions they had, Chrome began displaying all active extensions to the right of the omnibox. Users could "overflow" extensions into the Chrome menu if they wanted.

![]()

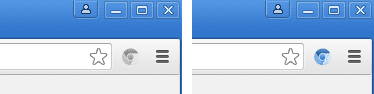

In order to display an icon for each extension, this update also ushered in two important changes to how extensions behaved in Chrome's UI. First, all extensions began displaying icons in the toolbar. If the extension didn't have an icon, Chrome would autogenerate one for it. Second, page actions moved into the toolbar alongside browser actions and were given an affordance to differentiate between their "show" and "hide" states.

This change allowed page action extensions to continue working as expected, but it also diminished the role of page actions over time. One of the effects of the UI redesign was that page actions were effectively subsumed by browser actions. Since all extensions appeared in the toolbar, users came to expect that clicking an extension's toolbar icon would invoke the extension, and browser actions became an increasingly important interaction for Chrome extensions.

Manifest V3 changes

The Chrome UI and extensions continued to evolve in the years following the 2016 extension UI redesign, but browser actions and page actions remained largely unchanged. That is, at least until we started planning how to modernize the extensions platform with Manifest V3.

It was clear to the extensions team that browser actions and page actions were increasingly a distinction without meaning. Worse, their subtle behavior differences made it hard for developers to determine which one to use. We realized that we could address these issues by combining the browser action and page action into a single "action."

Enter the Action API; chrome.action is most directly analogous to chrome.browserAction, but it

has a few notable differences.

First, chrome.action introduces a new method named getUserSettings(). This method

gives extension developers a way to check if the user has pinned their extension's action to the

toolbar.

let userSettings = await chrome.action.getUserSettings();

console.log(`Is the action pinned? ${userSettings.isOnToolbar ? 'Yes' : 'No'}.`);

"getUserSettings" may seem like a bit of an unusual name for this functionality compared to, say, "isPinned", but the history of actions in Chrome shows that the browser UI changes faster than extension APIs do. As such, our goal with this API is to expose action-related user preferences on generic interfaces in order to minimize future API churn. It also lets other browser vendors expose browser-specific UI concepts in the UserSettings object returned by this method.

Second, the icon and enabled/disabled state of an extension's action can be controlled using the Declarative Content API. This is important because it lets extensions react to the user's browsing behavior without accessing the content or even the URLs of the pages they visit. For example, let's see how an extension can enable its action when the user visits pages on example.com.

// Manifest V3

chrome.runtime.onInstalled.addListener(() => {

chrome.declarativeContent.onPageChanged.removeRules(undefined, () => {

chrome.declarativeContent.onPageChanged.addRules([

{

conditions: [

new chrome.declarativeContent.PageStateMatcher({

pageUrl: {hostSuffix: '.example.com'},

})

],

actions: [new chrome.declarativeContent.ShowAction()]

}

]);

});

});

The above code is almost identical to what an extension would do with a page action. The only

difference is that in Manifest V3 we used declarativeContent.ShowAction instead of

declarativeContent.ShowPageAction in Manifest V2.

Finally, content blockers can use the declarativeNetRequest API's

setExtensionActionOptions) method to display the number of

requests blocked by the extension for a given tab. This capability is important because it allows

content blockers to keep end users informed without exposing potentially sensitive browsing metadata

to the extension.

Wrap up

Modernizing the Chrome extensions platform was one of our major motivations for Manifest V3. In many cases that meant switching to new technologies, but it also meant simplifying our API surface; that's what our goal was here.

I hope this post helped shed some light on this particular corner of the Manifest V3 platform. To learn more about how the Chrome team is approaching the future of browser extensions, check out the Platform vision and Overview of Manifest V3 pages in our developer documentation. You can also discuss Chrome extensions with other developers on the chromium-extensions Google Group.